Establishing the postal system

A makeshift roadside sorting point ‘somewhere in France’. Mail bags, brought from an APS depot on the coast, are being unloaded from a mail truck, and the mail is being sorted on the table to the left, ready for delivery to the troops stationed nearby. The mail truck returned to the APS depot with sacks of homeward bound mail.

Image © The British Postal Museum & Archive

Soldiers and their families kept in touch by sending letters, postcards and parcels. For Fred and Arthur, on active service on the Western Front, their link with home was through the Field Post Office (FPO) – a post office set up in the field by the Army Postal Service (APS).

When the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) left for France in August 1914, members of the APS went with the troops, and within days FPOs had been established and letters were being sent and received by the sack load. During that first month of war, BEF troops were able to send letters home at a special rate of 1d (one penny) a letter – the usual rate from France to Britain was 2d (two pennies or tuppence).

However, troops posted large numbers of letters unstamped, leaving the recipient at home to pay the postage, plus a postage due surcharge.

At the end of August 1914, the issue of unstamped mail was raised in the House of Commons and the Postmaster-General, Mr Charles Hobhouse, announced:

"It has been decided by the Government that in future all letters written by soldiers on active service may be sent to this country without any prepayment by the soldier, and without any charge being made upon the recipient of the letter. In other words, correspondence written by the soldier on active service to his relations or friends will be carried free of charge.”

(Hansard, 31st August 1914)

The postal system – outward bound

In theory, it took only two days for a letter posted in Britain to reach France – but then came the onward journey to named troops somewhere in the field.

At its peak, the Army Postal Service was handling as many as 12 million outward bound letters and 1 million parcels every week. Inevitably some were “lost in the post", as evident from Fred’s letter of 5th July 1915 when he says: "Please put on my address Signal Section Head Quarters. Perhaps I shall receive all my letters then.”

On 8th December 1916 Fred says: "Don't write anymore until I let you know. I expect your letters have gone west this last week or two.”

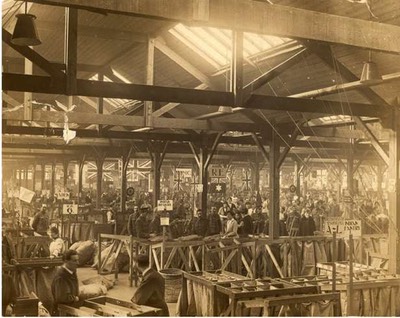

Outward bound mail began its journey to the Western Front at the Home Depot, a purpose-built sorting depot in Regent’s Park, London.

Covering some five acres, the Home Depot was said to be the largest wooden structure in the world, employing more than 2,500 staff, most of whom were female.

Mail came to the Home Depot from all parts of Britain. Each morning Whitehall informed the Home Depot of the latest movements of the Army's units, and also the Navy’s ships, so each item of mail could be dispatched to the correct location of the troops.

The mail was sorted by hand, but if a letter or parcel wasn’t properly addressed, delays occurred. Some parcels arrived damaged and had to be repackaged before they could be despatched.

Mail bags were filled and labelled, then taken by train or lorry to the Channel ports of Southampton and Folkestone, where they were loaded onto transport ships for the crossing to France.

The ships docked at the three BEF base depots established on the French coast at Le Havre, Boulogne and Calais.

From the base depots the mail bags were transported by supply train and lorry, along with munitions, to divisional refilling points at the Front.

Postal orderlies opened the mail bags and sorted through the mail, which was then taken on the final leg of its journey.

The aim was to hand out letters with the evening meal. No matter how tired and hungry the troops were, they always read their letters before eating. Evening was also the time, if possible, to write letters home. In one of Fred’s letters we find him writing home at "about 8pm” – it was Christmas Day 1915.

The postal system – homeward bound

Homeward bound mail took the reverse route – with one important additional step: the Army censor.

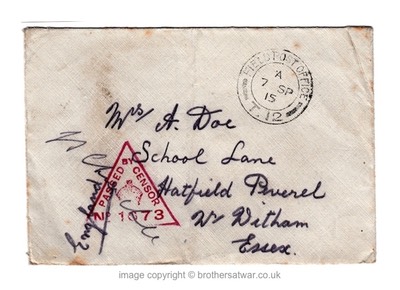

Troops handed their mail in at the Field Post Office, where a junior officer read it and, if necessary, censored it.

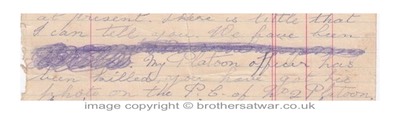

Sensitive information was struck out (“redacted” in today’s terminology), or simply cut out. There are examples of both forms of censorship amongst the brothers’ letters.

Once passed by the censor, the letter was replaced into its envelope, stamped with the censor’s cancellation, signed by him and given the Field Post Office cancellation.

The letter’s homeward journey could then begin, back to a BEF base depot at the coast, transported across the Channel, and then to the Regent’s Park Home Depot for sorting.

A few days after Fred and Arthur wrote their letters from “Somewhere in France”, “The Same Address”, “The Piggery”, or a Canadian hospital at Le Tréport, they were delivered to their family at School Lane, Hatfield Peverel, Essex.

Just as letters didn’t always reach the brothers, the same was true for their letters going home, as we see in Fred’s letter of 10th January 1916 when he says: "I don't quite understand why you haven't heard from me lately. I always answer your letters. But I suppose they go astray like a good many more.”

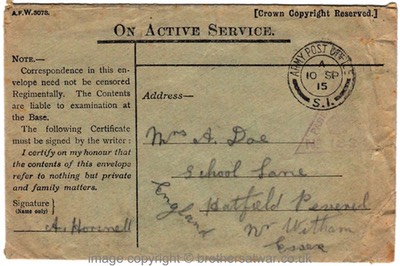

Honour envelopes – Army Form W.3078

Not every letter was subjected to scrutiny by the Army censor. Troops were allowed to send one uncensored letter a week, using a “Special Green Envelope” (Army Form W.3078).

A note on the front of the envelope made it clear how the envelope was to be used:

“Correspondence in this envelope need not be censored Regimentally. The Contents are liable to examination at the Base.

“The following Certificate must be signed by the writer:

I certify on my honour that the contents of this envelope refer to nothing but private and family matters."

These so-called "honour envelopes" were issued at the rate of one per man per week, and both Fred and Arthur sent letters home in them. There were no restrictions on how many letters the envelopes could contain and, unsurprisingly, troops filled them to the full.

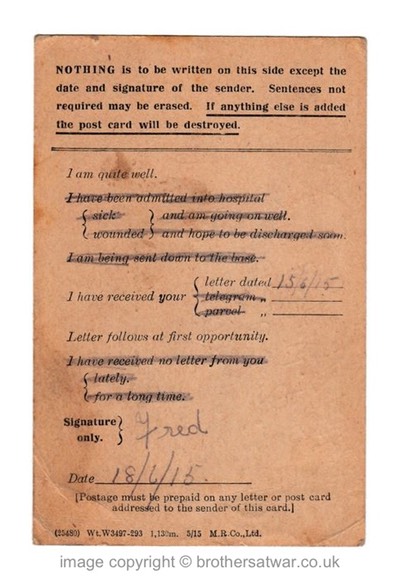

Field Service Postcard – Army Form A.2042

A quick and easy way to write home was by using the Field Service Postcard (Army Form A.2042).

This pre-printed postcard was designed to do no more than send the minimum amount of information which, when troops were at the front line, was sometimes about as much as they could manage.

The back of the postcard carried instructions for use:

“Nothing is to be written on this side except the date and signature of the sender. Sentences not required may be erased. If anything else is added the post card will be destroyed.”

A similar warning was printed on the front:

“The address only to be written on this side. If anything else is added the post card will be destroyed.”

For an excellent illustrated account of the Army Post Office in the First World War, visit

Picture Postcards from the Great War 1914–1918 (www.worldwar1postcards.com)

Selected sources

How did 12 million letters reach WW1 soldiers each week?

BBC iWonder: www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zqtmyrd#z3kc7ty

World War One: How did 12 million letters a week reach soldiers?

BBC News Magazine, 31st January 2014: www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-25934407

The Post Office and the First World War

The British Postal Museum & Archive: www.postalheritage.org.uk/page/firstworldwar

Army Form W8078 "Green Envelope”

Forum discussion about Green Envelopes: www.1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/index.php?showtopic=202054